Pinkas (Paweł) Rothenberg

My Great-Grandfather

The Elusive Pinkas Rothenberg

Once I began to search in earnest for mums family my ultimate goal was to connect with people who were living and breathing. Family I could communicate with in my own generation. One question led to another, and slowly, I began piecing together fragments of context. One of the biggest mysteries was the identity of Helena’s father - my great-grandfather. Who was he?

All that is known about Pinkas has been gleaned from lines in records and several passing mentions. Helena had listed her father as “Paweł” on her official wartime military record, but the first real clue to his identity surfaced on her 1951 marriage certificate to Baron Jan Konopka which I discovered in June 2014. There she recorded her father as “Paweł Rothenberg-Solomirecka,” landowner - deceased.

Glasgow based Jewish Genealogist Michael Tobias was the first to trace records revealing he was a member of the Jewish community the following August. Helena had listed her birthplace as Stryj, and named her mother as Franciszka Probst, allowing Michael to locate the records:

MT: You state that your mother’s [grand]parents were Pawel Rotenburgh-Solomirecka (Polish Landowner, deceased) and Franciszka Probst. Jews would not have used the names Pawel and Franciszka in everyday life – they would have used Yiddish or Hebrew names. Only for civil purposes (and where possibly trying to hide their Jewishness) would they have used such names. In many cases, their ‘Jewish’ names would have started with the same letter… So Pawel would be P…. and Franciszka would be F…….

Here we have a father called Pinkas (=Pawel) ROTHENBERG and a mother called Feiga Dwora (=Franciszka) PROBST, having daughters Roza and Malie in 1900 and 1902. Pinkas was from the town of Klodno. I can’t find a marriage record – perhaps they married elsewhere…. Pinkas is described as a director of a sawmill (so was relatively well-to-do).

‘Helena was fully Jewish. The 1900 and 1902 births I sent you were from the Stryj JEWISH REGISTRATION BOOKS. There is no doubt.

You do realise this actually makes you Jewish? Judaism passes down the mother’s line (you are never sure who the father is, but you always know who the mother is). Your grandmother Helena was Jewish and so therefore your mother was Jewish and hence you are Jewish...... and your children are Jewish!

Her family was 100% Jewish. Both the ROTHENBERGs and PROBST/PROPSTs were Jewish. These Jewish registers were only for 100% Jewish families. They would not be recognised as Jewish by the community if one of the parents was not Jewish.’

A few months after this fantastic breakthrough, I was able to trace Helena’s great nieces in the USA; they sent me their father, James Russocki’s memoirs. Pinkas, James grandfather, was mentioned, although not by name

“During the summer, I spent time with my maternal grandparents. I liked my grandfather a lot. I could not stand my step-grandmother. My real grandmother (Franciszka Probst) died of cancer when my mother was very young. My grandfather owned an estate and a lumber mill in the same part of Poland as we did. I found it interesting to go with him to the mill in the morning. He used to have the workers build me toys.

Every morning, thinking no one could see him, my grandfather took a shot of vodka just before breakfast. I knew, and probably all the servants knew it too. One day, after he left, I tried a shot of vodka myself. It burned all the way down to my toes, and I thought I was going to choke to death. I swore I would never drink alcohol again. So much for promises. I wonder if my grandfather knew I tried to imitate him—I think he probably did. He was a really very wise person.”

Reading this for the first time, I thought of my mum. How she would have loved to know her grandfather, maybe he would have taken a similar interest and had his workers make toys for her too… as far as we know, he only had two grandchildren. It also made me a little sad that James never knew the truth about his Jewish grandparents. His mothers silence however, almost certainly saved his life.

When Helena met my mother in a cafe in 1965, she confided in her daughter that her brother had been murdered by a Gestapo firing quad during the war. Despite sharing this with my new found American cousins, they had no knowledge their father had lost an Uncle. His mother, Irena had never mentioned she had a brother.

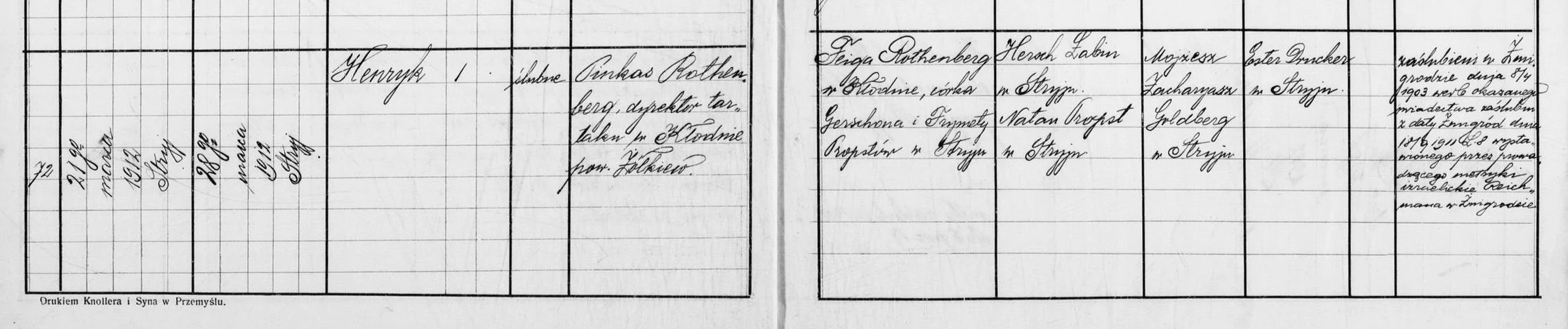

Amazingly, when new records from the community in Stryj were translated, Helena and Irena’s brother ‘Henryk’s’ birth record was found.

Henryk Rothenberg (translation)

Born: 21 March 1912, Stryj

Father: Pinkas Rothenberg, sawmill manager in Klodno (District of Żółkiew)

Mother: Feige Rothenberg (née Probst), daughter of Gerschon and Frymeta Probst of Stryj

Born in wedlock.

Parents married in Żmigród on 8 April 1903. Marriage certificate issued 18 September 1911 by Reichman, Registrar of the Jewish Metryka in Żmigród.

Pinkas was still managing the Klodno sawmill.

“During the summer, I spent time with my maternal grandparents. I liked my grandfather a lot. My grandfather owned an estate and a lumber mill in the same part of Poland as we did. I found it interesting to go with him to the mill in the morning. He used to have the workers build me toys.”

Image found in Pinkas’ daughters archive

Is this Pinkas and his Lumber Mill? (found in his daughters photo archives)

Despite these promising discoveries, three years passed, and we found nothing more to identify Pinkas’ Rothenberg family. I kept searching. I kept praying - why couldn’t we find Pinkas……?!

Michael Tobias kindly kept his ear to the ground. Polish researcher Maciej Kolski from Polish Ancestors hunted through tax records and civic archives. Even Janusz, my helpful neighbourhood Polish historian, joined the effort. Yet the result was always the same: silence. Pinkas - or Paweł - remained stubbornly elusive.

Whilst searching my Polish researcher, Maciej Kolski, discovered a record of a sawmill near Stryj in Dobrohostów (modern-day Dobrohostiv, Ukraine), owned by a ‘Leon Rothenberg, Scheinfeld, and Armbruster’….

‘Partners Marcin Armbruster, Mechel Scheinfeld, and Leon Rothenberg continued their agreement of 30 October 1917 in Sambor to work together for another 5 years until 1922’.

The shared Rothenberg surname, occupation, and close geographic proximity suggested a possible family connection - perhaps brothers or cousins working in the timber trade….

The breakthrough finally came in July 2017 through a series of records tied to my grandmother’s first marriage to Gustaw Kożdoń, beginning in March 2017. Maciej found a record on Geneteka - “I think I may know where Helena married Kożdoń. I am not 100% sure it's them…. it appears that her surname was Rothenberg, I think they didn't "change" it to Solomirecka until Irena (Helena’s sister) married Count Russocki.”

“If I am right and this record really is Helena's first marriage certificate that would give us info about her parents, and it would move us closer to solving Helena's father's mystery” - Maciej Kolski.

05/04/2017, 13:01 - I just received an answer from Warsaw

Name of groom is: Gustaw Kożdoń

Name of bride: Helena Teresa Maria Anna Rotenberg

Helena married Gustaw on 23rd of November 1927 in Lwów. They added that Gustaw was probably a ski jumping trainer. They asked me why I want to receive a copy of that document and what my connection is to the Kożdoń family. They wrote that there are some "sensitive matters".

Full translation

Parish Record No. 57

Address: Teatyńska Street No. 10

Date of Marriage: 23 November

Groom:

Gustaw Adalbertus Kożdoń, Agronomist, son of the late Paweł and Anna Broda, born in Oderberg, residing in Lwów.

Born: 15 January 1901. Religion: Catholic.

Bride:

Helena Theresia Maria Anna (formerly) Rotenberg, daughter of Paweł (Industrialist) and +Franciszka Probst (deceased), born in Stryj, residing in this parish.

Born: 8 May 1907.

Religion: Catholic.

Address: Living temporarily in Lwów (hospitio)

Witnesses:

General Lepesy, major, age 64, residing at Karmelicka Street 14, apartment 4.

Remarks:

Certificate of freedom to marry from the parish of Delatyn, Book V, page 257.

Dispensation from the impediment of mixta religio (mixed religion) granted by the Metropolitan Curia of Lwów on 17 November 1927, No. 10403.

Dispensation from the second and third banns granted by the same Curia on 17 November 1927, No. 15336/27.

Legal prenuptial declaration between the groom and bride received on 23 October 1927.

Groom's parish: Brody.

Baptismal certificate of the bride from the Evangelical parish (i.e., Protestant) dated 21 May 1921, Book 4, page 144.

The marriage was solemnly blessed and recorded in the registers of the cathedral parish.

This record led to finding Helena’s conversion and then her baptism records. It was the latter that provided the breakthrough, and opened the door to trace her father’s family.

07/06/2017, 08:18

“Jennie, I've got the letter! I have Helena's baptism certificate in my hands - and guess - are there grandparents mentioned or not?…..”

Date of Birth: 8 May 1902

Date of Baptism: 15 October 1926

Name: Helena Theresia Maria Anna (Malie), 24 years and 4 months old

Father: Paweł Rotenberg, son of Zenenis and Rozalia (Zindel and Rozalia)

Mother: Franciszka Probst, daughter of Georg and Felicja (Gerschon and Frimet)

Baptized by: Rev. Stanisław Lachowski, Assistant Vicar of the Cathedral Parish

Notes: Conditional baptism carried out by Rev. Wolanski Tertius; confession and catechesis conducted by Rev. Wolanski Junior, newly ordained. Regarding holy conversion: recorded in the Registry of the Metropolitan Curia of Lwów on 12 October 1926, No. 7340.

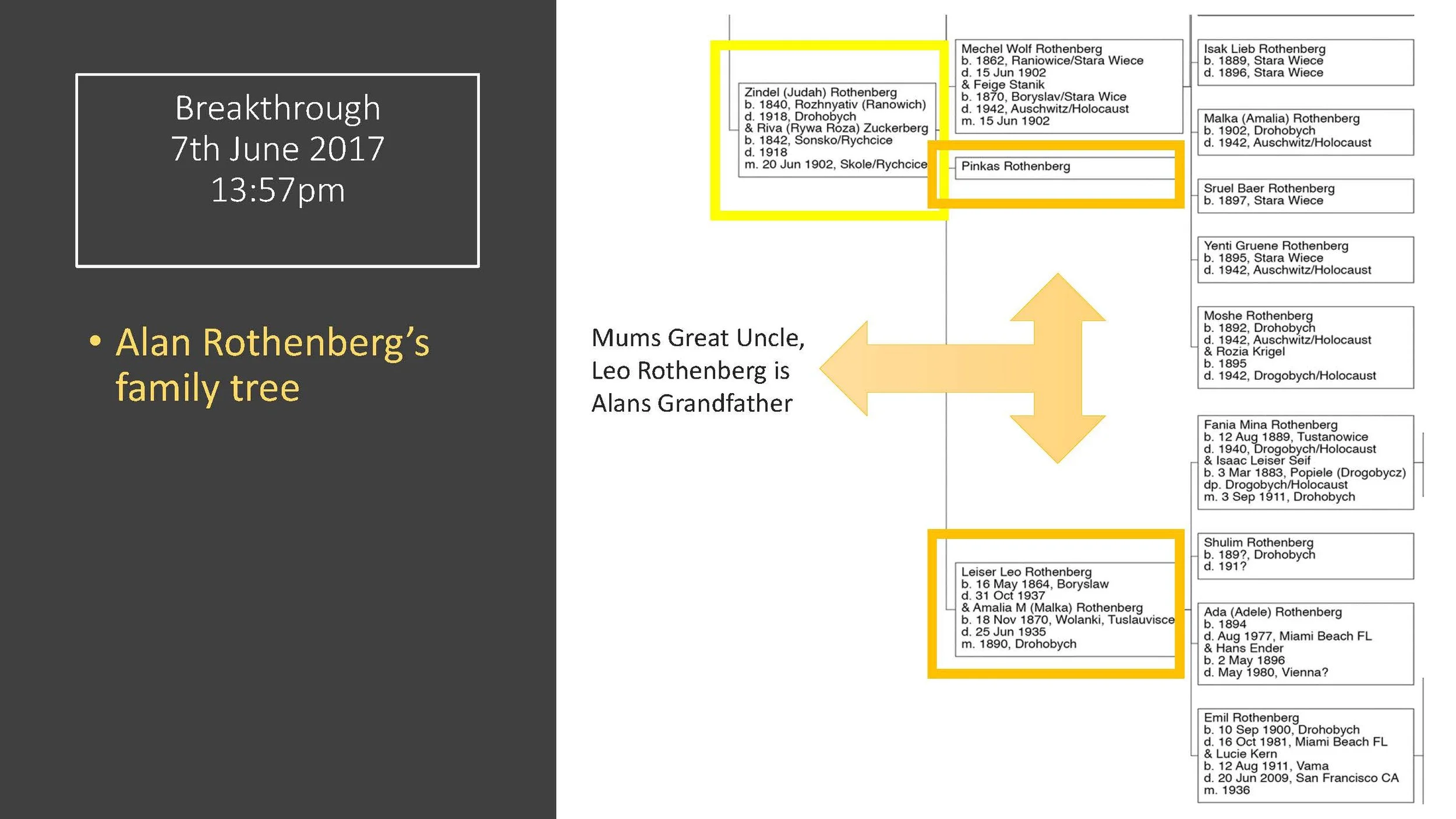

Just 30 minutes after I received the Baptism Certificate naming Pawel’s parents, I checked my DNA results which I had uploaded (after taking an Ancestry Autosomal test) to FTDNA a few days earlier. Unbelievably my top match appeared as a Rothenberg.

Initially, it seemed too good to be true. I was convinced this was Pawel’s family, Maciej tried to keep my feet on the ground..

I wrote immediately to my Rothenberg match’s genealogist, Karen Franklin, who responded, “Your email is really interesting. It's quite possible that you could be related to Alan Rothenberg, whose Rothenberg ancestors came from Drogobych, which is not far from Stryj. I'm not an expert in DNA - 100 centimorgans in common is not particularly significant, but a matching length of 18 is .. Please take a look at the attached family tree for Alan - we have no information about his great-grandfather's brother, Pinkas, so this is a possible connection.” Karen

According to Alan’s tree, Pinkas’ parents were Zindel and Rosa, and he had a brother, Leo or Leizer. Maciej reminded me he had found records for the owner of a sawmill called Leon Rothenberg, and thought that must be him.

07/06/2017, 15:28

“It seems that the brick wall starts to crack….” - Maciej

Yes! Michael Tobias thinks it's almost certain it's him

Alan messaged me and sent me a letter from his Aunt Ada, which mentioned her Uncle Pinkas, who called himself Paul. No one knew what had happened to him…

“Here’s a letter from my Aunt Ada that mentions Pinkus. Ada was a scholar and scientist (I believe the first woman to receive a PhD in Physics from the University of Berlin). Karen Franklin tells me you’re a second cousin, once removed, so we’re happy to share with you whatever information we have. Enjoy the journey.”

“Jennie, I think you should mark that day in your calendar as "Day of hitting jackpot". - Maciej Kolski

12/06/2017, 06:08

“Jennie

We have several sources in our family that have mentioned Pinkas, but no information on his birth date or place. Apparently, he was also known as "Paul", according to my aunt in a letter from 1975 describing a flock of relatives.

I assume he was born in or near Drohobycz. A number of folks in our family seemed to be in the brewery business in the later 1800's, and the region where they lived was an oil and timber centre, so there was probably lots of demand for their goods. If you learn more, we'd love to add it to what we know today.

My grandfather worked in the lumber business in the late 1880's and early 1900's, but lost everything in the Great Depression, at which time, he and my grandmother moved to Vienna, where my father, Emil, was then living. Both my grandparents died in the mid 30's and are buried in the Central Cemetery in Vienna, and my parents moved to the States in 1938, just after the Anschluss.

My wife, Susan, and I live in San Francisco” – Alan Rothenberg

Historical Context

The Rothenberg Brothers and the Timber Trade in Galicia

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the timber industry was one of the most vital sectors in Galicia, a region then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and later inter-war Poland. Towns like Stryj, Dobrohostów, and Żółkiew sat amid vast forests filled with pine, fir, oak, and beech, and along railways, making them hubs for wood processing and export, and supported an expansive network of sawmills, timber yards, and export routes. Timber from Galicia was in high demand across Europe for railway ties, mine props, construction, and paper pulp.

Jewish families played a central role in this trade. Although often restricted in land ownership, Jews operated as forest leaseholders, sawmill managers, timber exporters, and agents. Their work was supported by close community and family ties, often stretching across towns and generations. Jewish-run mills were especially active in regions like Stryj, Skole, Drohobycz, and Borysław, where wood could be floated down rivers or loaded onto new railways heading west.

Ownership of a sawmill was a sign of moderate to substantial prosperity. Some operations employed dozens of workers and included their own rail sidings or flume systems. Jewish families involved in such businesses often belonged to the urban middle class: educated, multilingual, and engaged in both religious life and the broader civic world. However, because many Jews lacked legal land ownership rights under imperial restrictions, they were often vulnerable to economic shifts or nationalisation efforts.

Records show that Pinkas, also known as Pawel, managed a sawmill in Klodno, in the district of Żółkiew, whilst it was eventually established through records and a DNA match with Leon’s grandson Alan, that Pawel’s brother Leon, also known as Leiser, co-owned a sawmill in Dobrohostów with two partners, Scheinfeld and Armbruster. The Rothenberg family's involvement in this industry reflects a common occupational pattern among Jewish families in Eastern Galicia, often owning or managing sawmills, lumberyards, and transportation routes.